Tarkovsky versus Kubrick

On the parallels between Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Andrey Tarkovsky's Solaris (1972)

Recently, I rewatched Andrey Tarkovsky’s Solaris, a 1972 film adaptation of the 1961 novel by Stanislaw Lem, which we read for my class on Soviet Science Fiction. What got me interested this time around was trying to pay attention to potential references to 2001: A Space Odyssey, sparked by a post on Tarkovsky and Kubrick from the 'gram:

Apparently, Tarkovsky despised Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, which Kubrick co-wrote with American SF writer, Arthur C. Clarke (this and the sequel 2010 are excellent). Tarkovsky called Kubrick a “phony” and his film “cold and sterile.” 2001 contained too many scenes of extrapolation, marking the mode of an older science fiction genre—a celebration of technology, its wanton display of future possibilities. *Look! A shiny new bauble!* Tarkovsky said the following, what is not altogether true of Kubrick’s film: “For some reason, in all the science-fiction films I’ve seen, the filmmakers force the viewer to examine the details of the material structure of the future.”

While he does present several scenes like this, Kubrick arguably keeps wanton extrapolation to a minimum, like in the Panam floating pen shots, etc. Kubrick does linger on the rotating Discovery One, but he does so to create atmosphere. The above doesn’t say anything about the estrangement qualities in 2001, its power to produce a certain aesthetic effect of awe chased by Tarkovsky himself. The sense of wonder from a cosmic alignment on the question of mankind’s origins is profoundly rendered in the film.

I think Tarkovsky is exagerrating, clearly showing a debt-via-critique to Kubrick (who actually admired Tarkovsky and listed Solaris and The Sacrifice in his top films). Watch Solaris with this in mind. You’ll notice several points of connection of clear homage to Kubrick’s 2001, I think done at the expense of Lem’s original novel. In other words, I believe Kubrick is the reason Tarkovsky deviates from the source material.

Take the scene of “Dr Haywood Floyd Moonbase Meeting” opening the plot of 2001, directly following the long safari “guided evolution” scenes. The discussion is about magnetic anomalies on the moon.

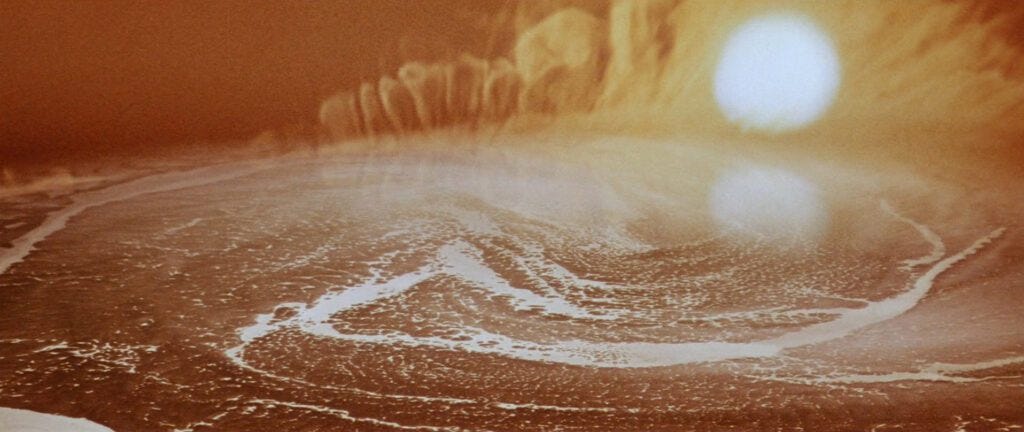

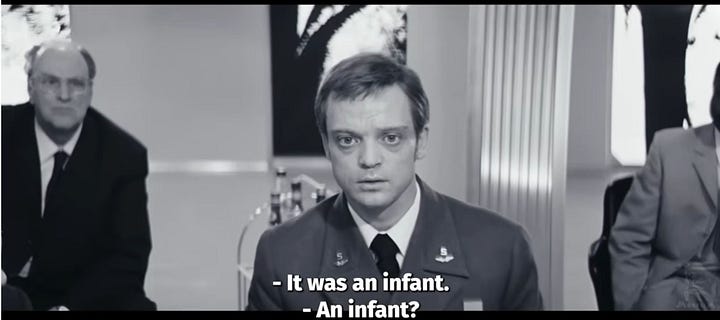

A similar briefing also opens Solaris, where the cosmonaut Burton tells about his visions on the planet’s surface—a giant 4-meter tall baby with blue eyes appears to him. It is the product of a memory of his child’s birth read off by the planet Solaris and materialized in plasma before his eyes, just like Rhey will be later (you kind of have to read Lem’s original to figure this out, but this child, now older, is actually playing on the grounds in the beginning of Solaris). The panel doesn’t believe the cosmonaut’s story and think Burton to be hallucinating; thus, Kris Kelvin, a psychiatrist qualified to sign off on such matters, is sent to Solaris to determine the truth. This is what starts the Solaris narrative, but is it not also a wink at Kubrick by Tarkovsky, one of several? Saying, hey, look how I can incorporate the profound lengths of your film, like the “starchild” into mine!

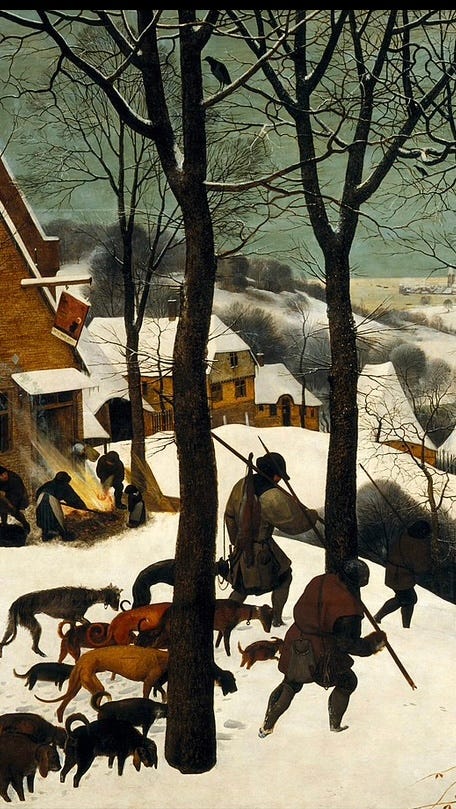

The fact that Kubrick used Bach and other classical music pieces seemed to annoy Tarkovsky, too. He opted instead, frustratingly, to near total absence of extradiagetic sound, no music, few dubbed sounds and dialogue, except for a few key scenes (this is what makes the film drag the most). However, Tarkovsky has his own version of nods to masters of other media. Instead of Bach, we get the Tarkovskian hovering eye and the contemplative/stupifying rendering of 2-D works in the motion of cinema (this appears in films like Andrey Rublev, where the icon painter’s works get a twenty-minute treatment). Instead of a hallucinogenic final sequence in 2001, here we get Breugel’s “The Return of the Hunters.”

To understand the movie, we need to answer what this painting signifies, as it becomes the entryway to the final movement of Solaris. That’s the rub that reveals the mysterious ending. Kelvin will be returning from the “hunt” to his father empty handed, just like the figures in the painting. In other words, the expedition, the hunt, was a failure. He has learned little about the planet, only gaining further questions about himself, annoying and likely unanswerable ones, by the end of his suffocating reunion with Hari (or Rhea in the novel). And so, Kelvin “decides” to stay on Solaris, opting for the phantasmatic version of his father instead of facing repercussions with the “real father” (i.e., the board) back on earth.

What’s interesting about Solaris is the range of interpretations it can accommodate. Hari is a piece of the sentient ocean that becomes self-aware, separated from the “collective," individuated in her love for Kelvin. Hence her suicidal gestures in order to protect him from the suffering she’s causing, which she comes to realize, and yet is completely innocent of. There is something queer perhaps to Hari. She doesn’t belong anywhere. She is a product of social and mysterious forces that she ultimately rejects, while Kelvin is totally beholden to them. Tarkovsky deviates from Lem’s original novel by twisting radical otherness—impossible contact that remains to the last page impossible—to a religious meditation on fathers and sons (and at the expense of a feminine presence). This deviation further indexes Tarkovsky’s own motivations to present his one-up of Kubrick. Tarkovsky draws closer to the themes of “contact with fathers” broached in 2001 and veers further away from Lem’s original ambiguity.

Anyway, these are just a couple parallels I noted recently, and I admit that I found Tarkovsky tedious, by today’s ambarassing standards of attention anyway, what I felt tugging at me when I had to screen the film. Despite the difficulty, I also found myself repeatedly amused by potential Kubrickian connections. For both Tarkovsky and Kubrick, good science fiction (or fantastika) is fundamentally about the human condition, an exploration of human depths with the help of fantastical and technological objective correlatives. Stating that Tarkovsky’s answer to Kubrick created something totally different from 2001 would be wrong. In some sense, Tarkovsky extrapolated on Kubrick, is closer to him than Lem, because they share in a common worldview.